Universal design (UD) is widely promoted as a strategy for creating environments that can be used and experienced by diverse users without requiring adaptation. Despite the growing availability of UD guidance, its integration into routine architectural practice remains inconsistent. This study investigates how practicing architects in Flanders, Belgium, perceive the key barriers and drivers influencing the decision to adopt UD at the beginning of the design process. A questionnaire survey was administered between January and June 2015 to architects attending five professional seminars organized by the Flemish architects’ association (Netwerk Architecten Vlaanderen), including two UD-focused sessions and three non-UD sessions. The instrument combined closed-ended items and open-ended prompts to examine architects’ prior experience with inclusive projects, perceived obstacles to initiating UDing, and motivations for adoption (Ielegems, et al., 2019). Of 396 distributed questionnaires, 127 valid responses were analyzed (32% response rate). Nearly half of respondents (48%) reported having worked on at least one inclusive project, with an average involvement of approximately 3.8 projects, suggesting that UD is applied selectively rather than as a standard approach. A majority (57%) reported barriers to adopting UD, with budget constraints and skeptical stakeholder attitudes—especially clients—emerging as the most challenging. Architects with UD experience reported fewer barriers overall, particularly regarding how to start UD processes and how to translate UD knowledge into design decisions, while stakeholder resistance remained persistent. Respondents also emphasized the lack of clear, structured, design-relevant UD information and the perceived complexity of integrating UD alongside multiple regulatory and contextual constraints. Among architects reporting no barriers, adoption was primarily driven by personal values, perceived improvements in architectural quality, and social responsibility. The findings indicate that strengthening client and stakeholder understanding, providing practical and stage-specific UD guidance, and improving coherence across regulatory requirements are critical to advancing UD as a routine architectural design strategy.

Designers have a significant social responsibility because what they create can either welcome people in or unintentionally shut them out. When products, services, and buildings are planned to work for everyone, design can actively support a more inclusive society. In practice, though, many designers still treat their own bodies, capabilities, and everyday experiences as the default benchmark for decision-making (Crilly and Clarkson, 2006; Imrie, 2003; Zeisel, 2006). Even when they try to respond to a wider range of users, they often struggle to fully grasp—or effectively design around—the needs and realities of people whose lives differ greatly from their own (Eisma, et al., 2003). As a result, individuals who do not fit “typical” assumptions may be left out (Gray, et al., 2003; Imrie, 2003).

Universal design (UD)—along with closely aligned approaches such as inclusive design and design for all—offers a way to deliberately shape designs so they work for diverse users. UD has been defined as “a design strategy resulting in an environment, a product, or a service in which users do not need to adapt but instead are supported in their actions and experiences in a positive and elegant way” (Herssens, 2014; translated from original). Importantly, UD is not simply a final feature set or an end-state; it functions as a guiding approach that extends across the full design trajectory (Ielegems and Froyen, 2014; Ielegems, et al., 2015). The concept of universal designing (UDing), introduced by Steinfeld and Tauke (2012), further highlights UD as an ongoing, continuous activity of shaping and refining the built environment (Steinfeld and Maisel, 2012). Within UDing, regular input from users repeatedly feeds into design decisions, helping teams move toward more inclusive outcomes over time (Ielegems, et al., 2015).

At its core, UD seeks to bring the viewpoints of actual, varied users into the heart of the design process (Suri, 2007). Yet, despite the expanding research base on UD and the development of many UD tools and techniques across design fields (Goodman-Deane, et al., 2014; Langdon, et al., 2015), UD still does not appear to be widely embedded or consistently practiced throughout design workflows in many parts of the world (Dong, et al., 2003; Fletcher, et al., 2015). The everyday habits, professional routines, and established mindsets through which architects design may shape whether—and in what ways—they engage with UD methods during the full process (Cross, 2006; Lawson, 2005; Symes, et al., 1995). For that reason, this paper seeks to better understand the perceived factors that hinder or encourage practicing architects to begin designing with human diversity in mind. Building a detailed picture of the obstacles and constraints behind limited UD uptake is essential if the field is to meaningfully improve implementation in practice (Sandhu, 2011).

Research across multiple design fields has explored why universal design (UD) is either embraced or resisted in everyday practice. In this study, UD barriers are understood as any obstacles within the design process that block inclusive outcomes, while UD drivers are the influences that attract designers toward UD rather than forcing compliance. Drawing on work from domains such as architecture, industrial design, and information and communications technology (ICT), the literature commonly groups these influences into three broad sets: attitudinal, practical, and knowledge-related.

The motivations that encourage designers to apply UD are often tied to personal and professional values—such as respect for human dignity, fairness, equal opportunity (Lid, 2013:47), social responsibility, and long-term sustainability (Ryhl, 2014). By contrast, one of the most frequently reported attitudinal obstacles is an incomplete or superficial grasp of what UD actually entails among designers and other stakeholders (Bringolf, 2011; Fletcher, et al., 2015; Larkin, et al., 2015; Yusof and Jones, 2014). When UD is not well understood, it becomes difficult for designers to adopt a mindset that consistently seeks refined, high-quality solutions that work for everyone throughout the full design cycle.

A recurring theme is the tendency to reduce UD to “accessibility” alone (Steinfeld and Maisel, 2012; Yusof and Jones, 2014). Accessibility is often framed—especially in environmental terms—as removing obstacles primarily to enable physical entry or basic access. UD, however, is broader in scope: it aims to create settings that can be meaningfully used and experienced by all people, not merely entered (Gossett, et al., 2009:440). UD is also frequently miscast as “design for special needs,” reinforcing the mistaken view that it is mainly about tailoring solutions to a small set of user groups. In reality, UD seeks to respond to the widest possible range of people through an approach that begins with the mainstream and then expands outward to include everyone (Bringolf, 2011; Dong, et al., 2003; Vanderheiden and Tobias, 2000).

These misunderstandings can lead to another perceived drawback: the belief that UD produces stigmatizing outcomes or forces aesthetic compromises (Bringolf, 2011; Dong, et al., 2004). Such perceptions can strongly discourage uptake. Yet, this view runs counter to UD’s core intent, which is to support elegant, high-quality environments while reducing stigma rather than creating it (Froyen, 2014).

Across the literature, the most commonly cited practical constraints are limited time and constrained budgets. This is particularly emphasized in industrial design, where both factors are repeatedly linked to weak UD implementation (Dong, et al., 2003). UD is often assumed to be more expensive (Bringolf, 2011; Dong, et al., 2004; Gray, et al., 2003; Mazumdar and Geis, 2003), and designers frequently believe that tight schedules and financial limits restrict key UDing activities—especially methods that directly engage users (Bruseberg and McDonagh-Philp, 2000; Goodman-Deane, et al., 2010). These pressures are closely connected to the amount of room the client allows within a specific project for iteration, research, and inclusive methods (Goodman-Deane, et al., 2010).

On the other hand, the practical influences that encourage UD are often framed in economic terms. In organizational settings, commercial incentives may outweigh purely social motivations. Accordingly, UD is frequently promoted through benefits such as access to larger or more profitable markets, stronger brand positioning, and increased potential for innovation (Dong, et al., 2004; Vanderheiden and Tobias, 2000). Multiple contributions have positioned UD as a catalyst for innovation, highlighting why it may appeal as a strategic choice rather than a moral obligation (e.g., Eikhaug, et al., 2010; Gheerawo and Bichard, 2011; Steinfeld and Maisel, 2012).

Studies focusing on product development often identify limited UD-related knowledge as a major impediment (Dong, et al., 2004). Designers also tend to require user information in particular forms—both in what it contains and how it is delivered (Dong, et al., 2015; Suri, 2007; Van der Linden, et al., 2016). A consistent finding is that available user data is frequently misaligned with designers’ everyday working methods and thought processes (Dong, et al., 2015; Lofthouse, 2006). In many cases, the information lacks a clear organizing message and does not effectively support how designers reason and make decisions (Choi, et al., 2006). It is also often presented in ways that feel distant from design practice and therefore difficult to translate into actionable choices (McGinley and Dong, 2011).

At the same time, knowledge can become a powerful driver when it is made explicit—through research evidence, standards, or guidelines—and when it is packaged in formats that designers can readily use within real projects (Dong, et al., 2015).

This study explores how architects in current practice perceive the barriers to, and incentives for, adopting universal design (UD) in Flanders, Belgium. It contributes to the existing understanding of attitudinal, practical, and knowledge-related factors in two specific ways. First, unlike much earlier work, it concentrates on what shapes the decision to commit to UD at the start of a project. This emphasis is intentional: early willingness to treat UD as a guiding strategy appears crucial for achieving inclusion (Bringolf, 2011; Ringaert, 2001). In addition, producing refined and high-quality solutions requires that detailed insights about a wide range of users be incorporated from the earliest stages of designing (Ielegems, et al., 2015, 2016). Second, the research is grounded in day-to-day architectural practice, where the policy environment currently contains both compulsory pressures and encouraging supports aimed at greater inclusion in the built environment. That combination makes it a valuable setting for examining what encourages or discourages architects from applying UD. The empirical component focuses on a single case—the Flemish region of Belgium—which reflects circumstances found in many other places (even though architecture is always shaped by location-specific conditions and regulations).

The Flemish situation also shares many similarities with broader international trends. Social and demographic shifts, including growing aging populations, have pushed policymakers in numerous countries to recognize the importance of buildings that enable participation rather than restricting it. Since the United Nations adopted the Standard Rules on the Equalization of Opportunities for Persons with Disabilities in December 1993 (UN General Assembly, 1993), accessibility and related governmental action plans have gained greater attention across Europe (Bendixen and Benktzon, 2015). Awareness of UD has expanded over time as well. Instruments such as the Tomar Resolution of the and the EIDD Stockholm Declaration (European Institute for Design and Disability, 2004) signal this rising European commitment to action and awareness.

Against this international background, Flanders incorporated new accessibility requirements into urban-planning regulations in 2010. These measures were designed to make public buildings—particularly those of at least 1,615 ft.\(^{2}\) (150 m\(^{2}\))—more usable and accessible (Ruimtelijke Ordening en Gelijke Kansen Vlaanderen, 2010). Private dwellings, however, are not subject to the same legal obligations. Similar to approaches used elsewhere (e.g., the Americans with Disabilities Act in the United States and Document M in Great Britain), Flemish rules have largely focused on minimum accessibility thresholds, especially those connected to wheelchair access. Although such requirements have become part of standard design procedures, they are often viewed unfavorably. For example, a survey of Flemish architects ranked these criteria among the ten most frustrating features of their profession (Netwerk Architecten Vlaanderen, 2012). This reflects patterns reported internationally, where accessibility standards are frequently seen as expensive constraints that limit creative freedom (Gray, et al., 2003; Larkin, et al., 2015; Mazumdar and Geis, 2003). Alongside mandatory rules that effectively push practice toward accessibility, the Flemish government has also introduced optional UD guidance intended to encourage broader inclusion in the built environment (e.g., Gelijke Kansen in Vlaanderen, n.d.; Inter, n.d.). This evolution—also observed in other European countries and in the United States (Skavlid, et al., 2013)—represents a meaningful policy transition away from narrow accessibility compliance toward approaches that explicitly seek to include a wide range of people within the built environment (Haugeto, 2013).

Even though some policy contexts clearly combine both “push” requirements and “pull” incentives to steer design toward more inclusive outcomes (Björk, 2009), many designers remain hesitant to adopt UD as a consistent design strategy. This paper therefore aims to clarify how practicing architects perceive the choice of whether to integrate UD into their design process. To do so, the authors administered a questionnaire survey containing both open- and closed-ended items to capture how architects in Flanders understand the barriers and drivers related to implementing UD-oriented processes. The following section outlines the data-collection approach, the questionnaire structure, and the sampling of participants. The results are then presented in three stages: (1) quantitative findings about respondents’ previous use of UD as a design strategy; (2) quantitative and qualitative evidence concerning the kinds of barriers architects report when attempting to implement UD; and (3) findings drawn mainly from qualitative responses provided by architects who reported no barriers to adopting UD. Together, the second and third parts highlight different criteria architects appear to apply when deciding whether a specific project warrants a UD process. The paper concludes with discussion and concluding remarks.

Between January and June 2015, the authors carried out a questionnaire survey with architects attending seminars organized by the Flemish architects’ association, Netwerk Architecten Vlaanderen (NAV). The survey was handed out at five NAV sessions that were open to members. Two sessions explicitly addressed universal design (UD) (group A), while three sessions were unrelated to UD (group B). This setup enabled the researchers to include both architects who were already engaged with UD topics and those without a specific prior focus (groups A and B, respectively). In the analyses, perceptions of UD were compared not only between groups A and B, but also between respondents who reported barriers to starting a UD process and those who reported none.

Both groups received the same questionnaire. For group B, however, a UD definition (aligned with the definition presented earlier in the paper) was added at the start. Group B participants also received a brief verbal explanation of UD’s general purpose, emphasizing how UD differs from accessibility to reduce confusion about terminology. This extra introduction was unnecessary for group A because those participants had already attended UD- and aging-in-place-related lectures. Fisher’s exact and chi-squared tests were used to check whether the two groups differed in sociodemographic characteristics, and these tests indicated no significant differences between groups in age, gender, or design experience.

Responses from the closed- and open-ended items were analyzed using SAS 9.3 and Microsoft Excel 14.1.0. Answers to open-ended questions were coded and examined following principles of constructive grounded theory (Strauss and Corbin, 1994).

The survey began by collecting background information (age, gender, profession, years of architectural practice, and the number of employees in the respondent’s firm). The next part examined participants’ involvement with UD in their daily professional work by asking about their concrete experiences (e.g., how many inclusive projects they had worked on, what types of inclusive projects these were, and the design phases in which they had been actively involved). The questionnaire then investigated whether respondents experienced attitudinal, practical, or knowledge-related barriers that made it difficult to initiate UDing.

Based on prior literature on UD barriers across several design areas (architecture, product design, and ICT), eight potential barriers were listed:

uncertainty about how to begin a UD process;

insufficient information available during the design process;

lack of clear and structured information;

uncertainty about how to translate UD knowledge into a design solution;

skeptical attitudes from other stakeholders (e.g., clients, contractors/builders, colleagues);

increased complexity in the design process;

time demands; and

budget constraints.

Space was included for respondents to add up to two additional barriers. Participants were asked to rank their three most important barriers, with rank 1 indicating the most difficult and rank 3 the least difficult among the three. An open-ended item then invited respondents to explain their experiences with each selected barrier in their own words and, where possible, to illustrate them with examples drawn from their personal design practice. Including open-ended questions can support interpretation of fixed-response items (Foddy, 1994; Reja, et al., 2003) and help uncover more complex perspectives and motivational influences (Foddy, 1994). Respondents who reported no barriers to initiating UDing were instead asked, via an open-ended question, to describe what factors encouraged them to adopt UD.

In total, 396 questionnaires were distributed and 135 were returned. Eight returned questionnaires were excluded because they were incomplete or contained inconsistent answers, resulting in 127 valid responses (32% response rate): 54 from group A and 73 from group B. Response rates differed substantially between groups, with group A at 47%—nearly double the 26% observed for group B.

Across the full sample, 59% of respondents were male. Ages ranged from 23 to 63 years (mean age 39), and respondents reported an average of 15 years of professional experience. When restricting the dataset to practicing architects (\(n=121\), excluding six respondents who were not professional architects), the sample did not differ significantly from 2014 statistics for architects registered with the Flemish Council of Architects (2014) in terms of age and gender. The sample did, however, include a smaller share of architects aged 60–69 than the council’s registry, which may be attributable to retired architects being included in the council’s list.

Before examining how respondents viewed the obstacles and incentives associated with adopting UD, this section first summarizes their direct experience with UD in everyday architectural practice.

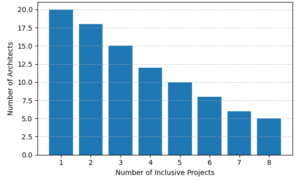

When respondents were asked whether they had ever worked on one or more inclusive projects—defined here as projects that pursued inclusion beyond simply meeting accessibility legislation—nearly half (48%) answered yes. Those respondents were then asked how many inclusive projects they had participated in; as shown in Figure 1, the average was about 3.8 projects. Regression analyses indicated that involvement with UD did not differ significantly by age, gender, or years of design experience. Likewise, there were no statistically significant differences between group A (participants attending a UD-related seminar) and group B (participants attending a non-UD seminar) in terms of whether they had worked on inclusive projects or how many such projects they had completed. Given that most respondents likely produced well over five projects during their careers (especially since the average experience level was 15 years), these findings imply that UD is not routinely applied as a default strategy on every project. Instead, architects appear to treat UD as an approach reserved for particular situations.

Respondents were also asked which stages of their inclusive projects they had been actively involved in (preparation and brief, concept, developed design, building permit, and/or tender and construction). A notably high share reported involvement across the full timeline, with average participation ranging from 78% (construction) to 92% (concept and developed design). In addition, about two-thirds indicated they were engaged throughout all design stages when working on inclusive buildings. This strong across-stage involvement may reflect the Flemish professional context, where many firms are small; architects therefore tend to stay closely connected to each project and follow it through rather than distributing design phases among many specialists.

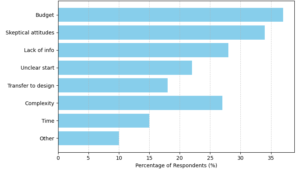

Overall, 57% of respondents (\(n=72\)) reported encountering barriers to adopting inclusive design strategies. Figure 2 summarizes the UD barriers reported. Because there were no significant differences between groups A and B in whether barriers were experienced or in the types of barriers reported, the authors combined the two groups for the analyses.

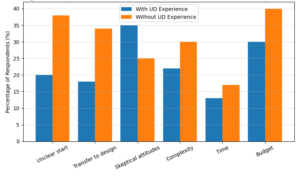

An important pattern emerged: architects who had already completed at least one inclusive project still reported obstacles, but they reported significantly fewer barriers overall (Figure 3). Among the eight listed barriers, the difference between those with and without inclusive-project experience was statistically significant for only two items: (i) being unclear about how to start a UD process, and (ii) being unsure how to translate UD knowledge into a concrete design.

Notably, “skeptical attitudes of other stakeholders” was the only barrier reported more frequently by respondents who had UD experience. This is understandable because stakeholder resistance is not something that disappears simply through an architect’s own experience. Differences between the two groups were also less marked for the time and budget barriers than for several other barriers (Figure 3). Looking across all barriers together, respondents who had completed more inclusive projects (two or more) tended to report fewer barriers overall.

Respondents were then asked to explain their barrier experiences in their own words and to provide practical examples from their work. The themes below reflect those open-ended responses.

Budget (37%) and skeptical attitudes of other stakeholders (34%) were identified as the two most difficult barriers (Figure 2). In the open-ended answers, many architects described how limited understanding of UD among stakeholders created significant challenges. Clients and other actors—such as colleagues, urban planners, local authorities, and contractors—did not always grasp UD’s purpose or value. Several respondents noted that this made it harder to persuade stakeholders to include more inclusive features. Stakeholders’ tendency to think in narrow “target group” terms also appeared to prevent them from seeing how UD could raise overall design quality for everyone.

Among all stakeholders, clients’ skepticism stood out as especially influential. Clients were directly referenced in 34% of all responses from participants who reported barriers. Because clients typically control the budget, respondents felt clients could strongly shape both the priorities and the decision-making direction of projects. As one respondent (no. 92) put it: “The client pays, so they decide how to spend the budget. They do not always understand the need for certain adjustments. This is why no adaptable house is being built despite this being possible.” This comment not only highlights the client’s financial power, but also shows how limited awareness of UD can become decisive when implementation requires additional effort. For example, some respondents reported that UD principles sometimes became less central than originally intended when inclusive solutions required more complex detailing (nos. 51 and 59) or extra planning (no. 109).

Surface area was also repeatedly mentioned in connection with budget—particularly when the client was not the end user. Respondents explained that “UD solutions generally require more space, resulting in clients being able to sell fewer square meters” (no. 86). Developers selling housing projects, for instance, often linked UD with increased floor area needs and therefore reduced profit.

Only 13% of those who reported barriers identified the amount of UD information as a problem. However, the third most commonly selected barrier (28%) was the absence of clear and well-structured information (Figure 2). In their open-ended responses, architects argued that UD knowledge was scattered across many sources, making it difficult to collect efficiently. Some also felt that existing materials were poorly formatted or too abstract, and that it was hard to locate the exact information needed at particular moments in the design process. Respondents mainly described obtaining UD knowledge through websites or guidelines, and they rarely referred to other indirect sources (such as research papers or books) or to direct engagement with users. This is noteworthy because studies have shown that user involvement can generate valuable insights that improve building quality (Eriksson, et al., 2014; Ringaert, 2001).

A further frequently reported barrier was the perception that UD increases process complexity (27%) (Figure 2). Respondents associated this complexity largely with contextual constraints and added requirements. Context-related limitations were often described as especially challenging, for example in renovations, protected monuments, and projects with tight surface-area limits (such as dense urban settings). Respondents suggested that design features linked to these contexts—multilevel layouts, narrow corridors, and steep staircases—were harder to adjust toward more inclusive solutions.

Complexity was also intensified by the need to align UD with multiple parallel demands. One respondent described UD as “yet another criteria that must be included from the very first design sketch, in addition to the program requirements, budget, energy efficiency, safety regulations, accessibility, fire prevention, etc.” (no. 120), indicating how the accumulation of requirements can significantly complicate the process. Respondents additionally pointed to tensions between Flemish accessibility regulations and other regulatory demands, including fire safety rules, monument protections, and energy-efficiency requirements.

Unlike prior studies that identify time pressures as a major obstacle to UD adoption (e.g., Sims, 2003; Vanderheiden and Tobias, 2000), “time-consuming” was one of the least selected barriers in this research (15%) (Figure 2). Here, budget was viewed as the primary constraint, while time appeared less decisive. Respondents did not typically frame time as causing delays in design or construction when UD was pursued. Instead, they linked time mainly to their own effort to build UD knowledge under tight deadlines. As one participant stated: “As an architect, [there is] not enough budget or time to conduct research yourself” (no. 90). In other words, time was discussed more as the architect’s personal investment within a project’s compensation structure than as a factor affecting the overall project timeline.

Among respondents who said they experienced no barriers (43% of the full sample), one small subgroup had never used UD (13%). Their explanations included: UD was not given attention, they lacked UD experience, or clients did not request it. A larger subgroup (35%, equivalent to 14% of the whole sample) reported that they consistently apply UD across all projects, while the remaining respondents (52%) said they use UD only sometimes. The next points focus on the latter two subgroups.

In open-ended responses, architects most often described motivations rooted in personal values. Some said they pursue UD to strengthen architectural quality and improve user experience, for example: “I am convinced that a house should be able to adapt to its users and not vice versa” (no. 47). Another frequently cited driver was social responsibility, often connected to designing sustainably for present and future generations. For some, social sustainability was a deciding motivation; one respondent (no. 117) remarked: “It often is not much extra work and results in a much more sustainable building.” Others referenced their own aging or life experience as a more personal reason to embrace UD. Overall, these architects tended to describe personal and social motivations—more than commercial incentives—as the main reasons they chose to begin UDing.

As noted earlier, most respondents did not treat UD as a default strategy applied automatically on every project. Among architects who reported no barriers and said they apply UD only sometimes, responses showed that they deliberately assess whether a UD approach is appropriate for a given commission. Many implied that a specific trigger is needed. One respondent (no. 126) captured this logic: “The basic philosophy is always nearby, but if there is no real need or reason for it, it will not be 100% respected.” Although the comment does not specify whether the “lack of respect” comes from the architect or other stakeholders, it points to the broader issue that sustained commitment depends on stakeholders recognizing UD’s value for the particular project.

Two dominant sets of criteria emerged: (1) design-related criteria and (2) client/budget criteria. Importantly, these criteria closely mirror the barriers described earlier. For design-related criteria, respondents without barriers frequently highlighted the existing context (e.g., constraints in the site or building) as a key factor in deciding whether to pursue UD. They also emphasized the building program as a selection criterion—an aspect not explicitly raised by respondents who said they faced barriers. Respondents additionally distinguished between public and private buildings, suggesting that UD’s relevance seems more obvious in public projects than in private ones, although the authors could not identify a single defining typology that clearly explained this distinction.

Finally, even when architects themselves believed UD would add value, client willingness—along with available budget—was repeatedly described as a decisive criterion for whether UD would be integrated from the start (a point that aligns with client influence being framed earlier as a barrier). Respondents explained that some clients avoid investing in UD because they do not see its benefits: “Making the client enthusiastic is the hardest thing to do” (no. 74). At the same time, responses suggested that when architects were personally convinced of UD’s potential, they often worked actively to persuade clients—an effort that appeared to distinguish respondents who reported no barriers from those who did. This more proactive, optimistic stance is illustrated by one respondent (no. 35): “Budget is an obstacle for many clients, but my own house is inclusive and is the best showroom to convince clients.” Overall, a more positive attitude toward UD and its possibilities seemed to be associated with fewer perceived barriers and a stronger inclination to initiate a UD process.

The findings indicate that, for many practicing architects, universal design (UD) is not yet embedded as a routine “default setting” in everyday work. Nearly half of respondents reported having contributed to at least one inclusive project, yet the mean number of inclusive projects (approximately 3.8) across careers with substantial experience suggests that UD is typically applied selectively rather than systematically. This pattern is important because it implies that UD is often approached as a situational response triggered by particular project conditions, rather than as a foundational strategy that consistently guides briefing, concept development, and detailing across all commissions. In this sense, the results reinforce the significance of early commitment: when UD is framed as optional or only relevant for certain projects, inclusive intentions are more likely to weaken as design decisions become constrained by program demands, regulatory requirements, time pressures, and cost limitations.

A key contextual insight concerns architects’ high level of involvement across design stages in inclusive projects. In the Flemish context—characterized by many small-scale architectural practices—architects often remain closely engaged from early concept work through construction. In principle, such continuity should support UDing because it enables architects to carry inclusive intentions across phases and translate them into decisions at multiple points (briefing, spatial planning, detailing, approvals, and execution). However, the persistence of barriers, even among architects with UD experience, shows that continuous involvement does not on its own remove the structural and relational constraints that shape whether inclusive ambitions become realized outcomes. Experience reduces certain uncertainties, but it cannot fully neutralize external pressures, particularly those arising from stakeholder skepticism, regulatory tensions, and budget control.

The pattern of reported barriers highlights that the strongest constraints are not merely technical. Budget and skeptical attitudes of other stakeholders were most frequently ranked as the most challenging barriers, indicating that UD adoption depends heavily on decision-making power beyond the architect. In particular, client priorities and willingness to invest appear decisive. Open-ended responses point to a recurring dynamic in which stakeholders interpret UD through a narrow “target group” lens, reducing it to a set of special provisions rather than a general quality-enhancing approach. This framing weakens perceived value and makes it more difficult for architects to argue for inclusive measures when they require additional space, more complex detailing, or extra planning. References to surface area and profitability further suggest that UD can conflict with business models that prioritize maximizing sellable floor area, particularly in developer-driven projects. Consequently, the most influential barrier may not be a lack of architectural capability, but the economic logic and risk perceptions that shape client decisions.

At the same time, the findings show that experience with inclusive projects is associated with fewer perceived barriers overall, especially those connected to uncertainty about how to start a UD process and how to translate UD knowledge into concrete design decisions. This suggests that part of the barrier landscape is developmental: practical exposure can build confidence, provide usable precedents, and reduce ambiguity in early-stage decision-making. However, the fact that stakeholder skepticism was reported more frequently by respondents with UD experience indicates that some barriers become more visible when architects move from intention to implementation, where negotiation with clients, contractors, and authorities becomes unavoidable. This points to a two-level challenge: strengthening architects’ competence and confidence while also improving the broader project ecosystem so that UD is not positioned as an unnecessary burden.

Knowledge-related findings identify a particularly actionable issue. Respondents were less likely to complain about the volume of UD information than about the lack of clear, structured, and design-relevant guidance. The reported fragmentation and abstract presentation of UD resources suggests a mismatch between how UD information is communicated and how architects work under real constraints. In practice, designers often need concise, stage-specific, decision-oriented guidance that can be applied during briefing, concept development, and detailing, rather than broad principles that require substantial interpretation. The limited mention of direct user engagement is also notable: despite evidence that user involvement can generate valuable insight, respondents predominantly referred to websites and guidelines as their information sources. This tendency may reflect time and fee structures that do not easily accommodate extensive research or structured user participation within typical project scopes.

Perceived complexity emerged as another central theme, particularly when UD requirements intersect with constrained contexts (renovations, protected monuments, dense urban sites) and when UD must be coordinated with multiple regulatory and performance demands (energy efficiency, safety requirements, accessibility rules, fire prevention, and others). Respondents explicitly referred to contradictions between accessibility regulations and other regulatory requirements, which can undermine confidence and create the sense that UD is “one more criterion” competing for attention from the earliest sketches onward. This insight has policy relevance: when regulations are experienced as inconsistent or as creativity-limiting constraints, they can encourage minimal compliance rather than meaningful inclusion. Improving coherence across requirements and offering clearer pathways for resolving conflicts may therefore be as important as further promoting UD.

An additional finding that contrasts with several earlier studies is that time was not among the most prominent barriers in this sample. Instead, time was mainly framed as the architect’s own investment in acquiring UD knowledge under tight deadlines, rather than as a factor causing delays in the overall project timeline. This distinction suggests that time becomes a barrier primarily when learning and research are not supported within budgets or fee structures. It also implies that improving the accessibility of practical, well-structured UD guidance could indirectly reduce perceived time burdens by reducing the effort required to search for, interpret, and justify inclusive measures.

The responses from architects who reported no UD barriers provide an important counterpoint. In these accounts, the most prominent drivers were linked to personal values, design quality, improved user experience, and social responsibility connected to sustainability across generations. For architects who applied UD only sometimes, the decision to adopt UD appeared to rely on identifiable “triggers” and selection criteria. Two broad categories—design-related criteria and client/budget criteria—mirrored the barrier landscape, suggesting that architects’ decision rules are shaped by the same constraints that inhibit implementation. Nevertheless, the data also imply that a more positive UD mindset can increase architects’ willingness to advocate for inclusion and attempt to convince clients, sometimes through demonstration and precedent. Such agency may represent a practical difference between architects who perceive barriers as decisive and those who perceive them as negotiable.

This study demonstrates that in contemporary architectural practice in Flanders, UD is not consistently applied as a standard design strategy, even though many architects have participated in inclusive projects and often remain involved throughout the entire design process. The results indicate that the most influential barriers to initiating UDing are concentrated around budget constraints and skeptical attitudes of stakeholders—especially clients—whose priorities strongly shape project direction and willingness to invest in inclusive measures. While architects with prior UD experience report fewer barriers overall, external barriers linked to stakeholder attitudes remain persistent and may even become more apparent as architects attempt to translate inclusive intentions into built outcomes.

The study also identifies a critical knowledge-related limitation: not a lack of UD information in general, but a lack of clear, structured, and design-relevant guidance that supports timely decisions across design stages. UD is further perceived as increasing complexity, particularly in constrained contexts (such as renovation, heritage protection, or limited urban sites) and when it must be reconciled with multiple, sometimes conflicting, regulatory requirements. By contrast, time was not reported as a dominant barrier in itself; rather, time pressures were mainly connected to architects’ personal effort to acquire applicable UD knowledge within tight project deadlines and limited compensation structures.

Overall, the findings suggest that improving UD uptake requires interventions that extend beyond architect-focused training alone. Meaningful progress is likely to depend on strengthening client and stakeholder understanding of UD as a quality- and value-enhancing approach, providing stage-specific and design-oriented UD information, improving coherence across policy and regulatory frameworks to reduce contradictions, and creating incentives or procurement structures that reward inclusion rather than treating it as an optional add-on. Finally, the results underscore that architects’ personal values and design attitudes can act as strong drivers—particularly when linked to architectural quality and social sustainability—and that positive narratives and demonstrated precedents may help shift UD from selective adoption toward more routine practice.

Bendixen K, Benktzon M (2015) Design for all in Scandinavia — a strong concept. Applied Ergonomics 46(B):248–257.

Bringolf J (2011) Barriers to universal design in Australian housing. Paper presented at the International Conference on Best Practices in Universal Design at FICCDAT. Toronto (5–8 June).

Bruseberg A, McDonagh-Philp D (2000) User-centred design research methods: The designer’s perspective. In PRN Childs and EK Brodhurst (Eds.), Integrating design education beyond 2000. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 179–184.

Choi YS, Yi JS, Law CM, Jacko JA (2006) Are universal design resources designed for designers? In S Keates and S Harper (Eds.), Assets ’06: Proceedings of the 8th international ACM SIGACCESS conference on computers and accessibility. New York: Association for Computing Machinery, pp. 87–94.

Crilly N, Clarkson PJ (2006) The influence of consumer research on product aesthetics. In D Marjanovic (Ed.), DS 36: Proceedings of DESIGN 2006, the 9th international design conference. Dubrovnik, Croatia: The Design Society, pp. 689–696.

Cross N (2006) Designerly ways of knowing. London: Springer.

Dong H, Clarkson PJ, Ahmed S, Keates S (2004) Investigating perceptions of manufacturers and retailers to inclusive design. The Design Journal 7(3):3–15.

Dong H, Keates S, Clarkson PJ, Cassim J (2003) Implementing inclusive design: The discrepancy between theory and practice. In N Carbonell and C Stephanidis (Eds.), Universal access: Theoretical perspectives, practice, and experience: 7th ERCIM international workshop on user interfaces for all, Paris, France, October 24–25, 2002, revised papers. Berlin: Springer, pp. 106–117.

Dong H, McGinley C, Nickpour F, Cifter AS (2015) Designing for designers: Insights into the knowledge users of inclusive design. Applied Ergonomics 46(B):284–291.

Eikhaug O, Gheerawo R, Plumbe C, Berg MS, Kunur M (2010) Innovating with people: The business of inclusive design. Oslo: Norsk Designråd.

Eisma R, Dickinson A, Goodman J, Mival O, Syme A, Tiwari L (2003) Mutual inspiration in the development of new technology for older people. Paper presented at the International Conference on Inclusive Design and Communications 2003 (INCLUDE 2003). London (18–25 March).

Eriksson J, Glad W, Johansson M (2014) User involvement in Swedish residential building projects: A stakeholder perspective. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment 30(2):313–329.

European Institute for Design and Disability (2004) The EIDD Stockholm declaration 2004. http:// dfaeurope.eu/what-is-dfa/dfa-documents/the-eidd-stockholm-declaration-2004/. Site accessed 24 March 2020.

Flemish Council of Architects (Orde van Architecten Vlaamse Raad) (2014) Statistieken van het ledenbestand van de orde (data files) (Dutch). Retrieved from http://www.ordevan architecten.be/orde/statistieken.php.

Fletcher V, Bonome-Sims G, Knecht B, Ostroff E, Otitigbe J, Parente M, Safdie J (2015) The challenge of inclusive design in the U.S. context. Applied Ergonomics 46(B):267–273.

Foddy W (1994) Constructing questions for interviews and questionnaires: Theory and practice in social research. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Froyen H (2014) Universal design: A methodological approach. In H Caltenco, PO Hedvall, A Larsson, K Rassmus-Gröhn, and B Rydeman (Eds.), Universal design 2014: Three days of creativity and diversity. Amsterdam: IOS Press, pp. 7–8.

Gelijke Kansen in Vlaanderen (n.d.) Handboek toegankelijkheid publieke gebouwen (Dutch). www .toegankelijkgebouw.be. Site accessed 24 March 2020.

Gheerawo R, Bichard JA (2011) Support strategy. New Design 87:32–37.

Goodman-Deane J, Ward J, Hosking I, Clarkson PJ (2014) A comparison of methods currently used in inclusive design. Applied Ergonomics 45(4):886–894.

Gossett A, Mirza M, Barnds AK, Feidt D (2009) Beyond access: A case study on the intersection between accessibility, sustainability, and universal design. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology 4(6):439–450.

Gray DB, Gould M, Bickenbach JE (2003) Environmental barriers and disability. Journal of Architectural and Planning Research 20(1):29–37.

Haugeto AK (2013) Introduction: Trendspotting at UD 2012 Oslo. In TD Centre (Ed.), Trends in universal design: An anthology with global perspectives, theoretical aspects and real world examples. Oslo: Norwegian Directorate for Children, Youth and Family Affairs, pp. 6–9.

Herssens J (2014) Universal design, ontwerpen met zorg voor iedereen (Dutch). Paper presented at the “Design for Health, Design with Care” interregional meeting. Hasselt, Belgium (4 December).

Ielegems E, Froyen H (2014) Universal design: A methodological approach. Design for All 9(10):31–42.

Ielegems E, Herssens J, Nuyts E, Vanrie J (2019) Drivers and barriers for universal designing. Journal of Architectural and Planning Research 36(3):181-97.

Ielegems E, Herssens J, Vanrie J (2015) AV-model for more: An inclusive design model supporting interaction between designer and user. In C Weber, S Husung, G Cascini, M Cantamessa, D Marjanovic, and M Bordegoni (Eds.), DS 80-9: Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Engineering Design (ICED 15), Vol. 9: User-centred design, design of socio-technical systems. Milan, Italy: ICED, pp. 259–268.

Ielegems E, Herssens J, Vanrie J (2016) User knowledge creation in universal design processes. In G di Bucchianico and P Kercher (Eds.), Advances in design for inclusion: Proceedings of the AHFE 2016 International Conference on Design for Inclusion. Basel, Switzerland: Springer, pp. 141–154.

Imrie R (2003) Architects’ conceptions of the human body. Environment and Planning D 21(1):47–66.

Langdon P, Johnson D, Huppert F, Clarkson PJ (2015) A framework for collecting inclusive design data for the UK population. Applied Ergonomics 46(B):318–324.

Larkin H, Hitch D, Watchorn V, Ang S (2015) Working with policy and regulatory factors to implement universal design in the built environment: The Australian experience. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 12(7):8157–8171.

Lawson B (2005) How designers think: The design process demystified, 4th edition. London: Architectural Press.

Lid IM (2013) An ethical perspective. In S Skavlid, HP Olsen, and AK Haugeto (Eds.), Trends in universal design: An anthology with global perspectives, theoretical aspects and real world examples. Oslo: Norwegian Directorate for Children, Youth and Family Affairs, The Delta Centre, pp. 46–51.

Lofthouse V (2006) Ecodesign tools for designers: Defining the requirements. Journal of Cleaner Production 14(15):1386–1395.

Mazumdar S, Geis G (2003) Architects, the law, and accessibility: Architects’ approaches to the ADA in arenas. Journal of Architectural and Planning Research 20(3):199–220.

McGinley C, Dong H (2011) Designing with information and empathy: Delivering human information to designers. The Design Journal 14(2):187–206.

Netwerk Architecten Vlaanderen (2012) Ons vak in vorm (Dutch). Gent, Belgium: Flemish Architects’ Association.

Reja U, Manfreda KL, Hlebec V, Vehovar V (2003) Open-ended vs. close-ended questions in web questionnaires. Developments in Applied Statistics 19(1):159–177.

Ringaert L (2001) User/expert involvement in universal design. In WFE Preiser and E Ostroff (Eds.), Universal design handbook. New York: McGraw-Hill, pp. 6.1–6.14.

Ruimtelijke Ordening en Gelijke Kansen Vlaanderen (2010) Stedenbouwkundige verordening betreffende toegankelijkheid (Dutch). https://www.toegankelijkgebouw.be/Regelgeving /Downloads/tabid/328/Default.aspx. Site accessed 26 March 2020.

Ryhl C (2014) The missing link in implementation of universal design: The barrier between legislative framework and architectural practice. In H Caltenco, PO Hedvall, A Larsson, K Rassmus-Gröhn, and B Rydeman (Eds.), Universal design 2014: Three days of creativity and diversity. Amsterdam: IOS Press, pp. 433–434.

Sandhu JS (2011) The rhinoceros syndrome: A contrarian view of universal design. In WFE Preiser and KH Smith (Eds.), Universal design handbook, 2nd edition. New York: McGraw- Hill, pp. 44.3–44.12.

Sims R (2003) ‘Design for all’: Methods and data to support designers. PhD dissertation, Loughborough University, Loughborough, UK.

Skavlid S, Olsen HP, Haugeto AK (Eds.) (2013) Trends in universal design: An anthology with global perspectives, theoretical aspects and real world examples. Oslo: Norwegian Directorate for Children, Youth and Family Affairs, The Delta Centre.

Steinfeld E, Maisel J (2012) Universal design: Creating inclusive environments. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Strauss A, Corbin J (1994) Grounded theory methodology: An overview. In KD Norman and SLY Vannaeds (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, pp. 273–285.

Suri JF (2007) Involving people in the process. Paper presented at the 4th International Conference on Inclusive Design (INCLUDE 2007). London (2–4 April).

Symes M, Eley J, Seidel AD (1995) Architects and their practices: A changing profession. Oxford, UK: Butterworth Architecture.

UN General Assembly (1993) The standard rules on the equalization of opportunities for persons with disabilities. http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/enable/dissre00.htm. Site accessed 26 March 2020.

Van der Linden V, Dong H, Heylighen A (2016) From accessibility to experience: Opportunities for inclusive design in architectural practice. Nordic Journal of Architectural Research 28(2):33–58.

Vanderheiden G, Tobias J (2000) Universal design of consumer products: Current industry practice and perceptions. Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting Proceedings 44(32):6–19–6–21.

Yusof M, Jones D (2014) Universal design practice in Malaysia: Architect’s perceptions of its terminology. In H Caltenco, PO Hedvall, A Larsson, K Rassmus-Gröhn, and B Rydeman (Eds.), Universal design 2014: Three days of creativity and diversity. Amsterdam: IOS Press, pp. 347–355.

Zeisel J (2006) Inquiry by design: Environment/behavior/neuroscience in architecture, interiors, landscape, and planning. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.