The Walled City of Lahore (WCL) represents a layered historic settlement whose architectural character and spatial structure have been shaped by successive political eras and major socio-demographic change after 1947. This study investigates the current condition and transformation of the historic urban fabric of Kucha Vahrian, a neighborhood selected through a pilot survey due to its mix of old and new residents, the coexistence of historic and non-historic buildings, and visible pressures from encroachment and commercial-led construction. Drawing on a literature-based framework, the study defines ten conservation parameters addressing materials, facade ornamentation, structural components, retrofitting compatibility, spatial additions, daylight and ventilation, original openings, infrastructure installation, plinth levels, and encroachments. These parameters were operationalized through a structured observation sheet applied to sixteen built units over a two-year field period (2018–2019) (Haroon et al., 2019), supplemented by semi-structured resident interviews and structured interviews with officials of the Walled City of Lahore Authority (WCLA) to examine awareness, governance, and regulatory implementation under the Walled City of Lahore Act (2012). Findings indicate that while elements of vernacular construction and decoration persist in some pre-partition structures, the overall fabric is deteriorating due to unregulated additions, loss of open and communal spaces, improvised utility lines, and reduced access to light and air. Interview evidence further reveals a significant disconnect between formal regulations and resident awareness, alongside constraints in technical guidance and funding that limit conservation beyond isolated pilot projects. The study argues for shifting from project-based interventions toward a sustained, community-engaged conservation process supported by permanent technical capacity, locally grounded training, and practical guidance on heritage-compatible materials and methods.

Lahore, Pakistan, has stood out as a major city on the Indian subcontinent since around 1000 C.E., and some scholars argue its origins may reach even further back (Shahzad, 2002). Its long-standing importance stems largely from its position along historic trade corridors, which drew merchants, artisans, and religious travelers. At the same time, it became a key stop for would-be conquerors advancing from the northwest toward Delhi. Although the city was first governed by Hindu Brahman authorities, over the following centuries it came under the influence of Muslim rule through the Sultanate and later the Mughal empires, until Sikh leaders established the basis of Sikh power in Punjab (Singh, 2007). These successive shifts in control shaped Lahore into a place where varied customs and traditions merged, producing a distinctive cultural mosaic and a deep interweaving of different ethnic communities. As a result, the Walled City of Lahore (WCL) represents a powerful symbol of an ancient cultural legacy rooted in many generations. Remarkably, parts of this historic urban structure—reflecting the refined identity of its local society—still remain, making the present condition and preservation of this rare and invaluable heritage an important subject for investigation.

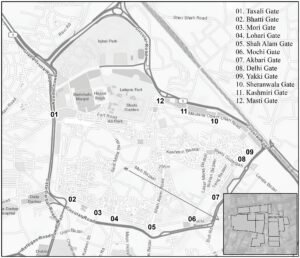

An examination of the WCL’s physical form shows clear parallels with other historic Islamic cities. Positioned near the Ravi River, it is enclosed by defensive walls punctuated by 13 gates (Gulzar, 2017). Over many centuries, habitation expanded within these boundaries, gradually forming a traditional city pattern defined by the enclosing wall, winding and irregular lanes, a royal fort, religious institutions, bustling bazaars, courtyard-based homes, and shared community spaces (Shahzad, 2002). This established order persisted until 1849, when Lahore came under British colonial rule. Historical accounts and scholarship indicate that the colonial period introduced far more extensive building activity, accompanied by straight, grid-like roads and an architectural shift away from culturally grounded forms toward administrative and institutional typologies (Rahmaan, 2017). By 1947—when the subcontinent was partitioned and Lahore became part of the newly created Pakistan—the city had evolved into a hybrid landscape combining vernacular traditions with colonial interventions (Kaur, 2006).

The partition and the formation of Pakistan triggered dramatic demographic upheaval. Sikh and Hindu groups, who made up about one-third of the WCL’s population, relocated to India (ibid.), and their departure was followed by the arrival of Muslim migrants (Qadeer, 1983) who moved into the abandoned properties. Although these structures provided essential accommodation for newcomers, the new occupants often had little historical or emotional connection to them (Shahzad, 2011). Studies indicate that while some present-day WCL residents descend from these migrants, many earlier inhabitants have since shifted to other parts of Lahore (Adeeb, 2018). In the context of historic Indian cities, both everyday residents and patrons—often represented by governing authorities—contribute to shaping the evolution of urban form. Therefore, the replacement and relocation of the local population played a major role in altering the WCL’s urban character. This careful and scholarly study examined those transformations by focusing on the historic urban fabric itself. The following section presents the literature review and introduces the ten parameters selected for the analysis.

Urban environments are commonly interpreted through five fundamental components: paths, edges, districts, nodes, and landmarks (Lynch, 1960). This conceptual framework is equally applicable to historic cities, which embody layered meanings derived from emotional attachment, cultural identity, and functional use accumulated over long periods of time (Feilden, 2003).

An examination of historic urban fabric provides insight into earlier civilizations, where architecture and spatial organization often expressed civic ideals as well as moral and spiritual values (Petruccioli, 2007). Built form has frequently served as a defining marker of civilizations; the pyramids of Egypt, the post-and-lintel systems of Greece, and the arches of Rome are emblematic examples (Freeman, 2014). In the Indian subcontinent, the medieval Mughal period represented a high point of architectural and urban development, particularly within the Walled City of Lahore (WCL), marked by advancements in construction materials, fabrication techniques, building orientation, load-bearing systems, and land-use organization (Gulzar, 2017).

Recent heritage studies have documented numerous historic settlements worldwide that demonstrate similarly rich urban characteristics. In Cairo, traditional residential buildings still feature mashrabiyyas, or projecting bay windows, reflecting Egyptian architectural traditions; however, many of these structures are increasingly threatened by large-scale concrete development. The historic core of Nicosia, Cyprus, enclosed by fortifications from Roman and Byzantine periods, has experienced deterioration in housing quality and environmental conditions due to rapid urbanization and political instability since 1974. In response, a strategic framework introduced in 2004 sought to recognize the area’s heritage value and reposition it as an economic and educational resource through tourism (Petropoulou, 2007).

In Hyderabad, India, the Chowmahalla Palace Complex—constructed in the mid-eighteenth century—underwent restoration in 2004 with a focus on adaptive reuse, relying extensively on the expertise of traditional craftsmen (Goad, 2005). Similarly, the Khan Alwakalah Restoration Project in Nablus, Palestine, involved the rehabilitation of a seventeenth-century caravanserai and its adjoining street, emphasizing minimal intervention through structural consolidation and careful facade restoration to preserve the building’s original character. Another illustrative case is the Kuzguncuk settlement along the Bosphorus, where a fifteenth-century urban fabric has been successfully preserved through public participation and strict government regulation, including legislation enacted in 1983 that restricts new construction to protect the historic skyline (Uzun, 2003).

Pakistan possesses a wide range of archaeological sites and monuments that collectively reflect a deep and diverse cultural heritage. This legacy can be traced back to ancient urban centers such as Mohenjodaro and Harappa, dating to approximately 2500 B.C., which exemplified advanced residential planning and influenced subsequent urban development across the region. Among Pakistan’s historic towns, Bhera—located on the banks of the Jhelum River—was already established by the time Alexander of Macedonia entered the subcontinent in 326 B.C. (Bukhari, 2016). The refined vernacular architecture of Bhera, distinguished by intricate wooden carvings, indicates its historical role as a cultural center (Aamir, 2018).

Uch Sharif, situated near Bahawalpur, represents another important historic settlement and contains numerous monuments, including the fifteenth-century Bibi Jawandi Monument Complex, which is currently undergoing conservation (Mumtaz, 2017). Prior to intervention, the site was evaluated through integrated assessments of visual, social, historical, and scientific values, alongside detailed analyses of construction materials, structural stability, and urban infrastructure. Saidpur Village in Islamabad provides a contrasting example of adaptive reuse, where a settlement approximately 500 years old has been redeveloped as a tourist destination featuring restaurants and a museum (Khan, 2015). However, the absence of professional conservation expertise has resulted in new construction that conflicts with the original fabric in terms of architectural language, materials, surface treatment, and building scale (Mumtaz, 2017).

In Peshawar’s Sethi Mohallah, surviving buildings and facade ornamentation still reflect the affluence and cultural richness of earlier residents, although many traditional structures have been demolished and replaced by austere concrete buildings. Ongoing conservation initiatives have identified non-historic constructions as hazardous and subject to removal (Heritage Foundation of Pakistan, 2012). Within the WCL itself, the rehabilitation of Gali Surjan Singh serves as a notable example of a deteriorated historic neighborhood that has been substantially improved through discreet infrastructure integration, housing repair, and facade restoration (Salman, 2018).

A synthesis of the reviewed literature and case studies indicates that effective conservation initiatives must be grounded in comprehensive social, architectural, and physical analyses of historic sites. Drawing from these insights, ten parameters were identified to examine transformations within the historic urban fabric of the WCL.

Brick has historically been the primary construction material in the region due to its availability, structural strength, and durability. Evidence from the late nineteenth century suggests that affluent households constructed fired-brick buildings finished with chuna, or lime mortar (Cowell, 2016). Accordingly, the retention of original construction materials constitutes the first parameter.

Pre-colonial facades in the study area commonly display elaborately carved wooden doors, jharokas, and lamp niches, with exterior ornamentation often signifying the social status of the owner (Glover, 2007). During the colonial period, an Indo-European architectural vocabulary emerged, combining local traditions with European elements such as arches, pilasters, moldings, jali work, balconies, and pediments (Ovais, 2016). The preservation of facade ornamentation therefore forms the second parameter.

Prior to British rule, vernacular buildings in Lahore relied on load-bearing brick walls supporting wooden spans, with openings framed by timber lintels. Structural systems evolved in the late nineteenth century with enhanced load-bearing configurations (Glover, 2007). Notably, many structural elements were integrated aesthetically into wall elevations, blurring the distinction between architectural and structural components. The preservation of these original structural elements defines the third parameter.

Building deterioration over time often necessitates structural strengthening; however, retrofitting can be problematic if later additions are incompatible with the original construction system (Feilden, 2003). The fourth parameter therefore evaluates the appropriateness of retrofitting interventions.

Spatial extensions in historic areas frequently arise from population growth and evolving lifestyles, including increased indoor living requirements (Khalid and Sunikka-Blank, 2018). When poorly executed, such additions compromise authenticity. Avoiding flawed spatial expansions constitutes the fifth parameter.

Access to daylight and ventilation is fundamental to residential quality. Historic buildings often incorporated openings positioned to optimize sunlight and airflow (Feilden, 2003). Unplanned additions can obstruct these natural elements; therefore, the retention of light and ventilation forms the sixth parameter.

Vernacular architecture traditionally employed solid wood for doors and windows, with regional craftsmanship producing intricate carvings and refined detailing (Singh, 2009; Aamir, 2018). The preservation of original openings is identified as the seventh parameter.

Historic buildings originally required minimal infrastructure, and narrow streets accommodated limited services without visual intrusion (Shahzad, 2002). Contemporary infrastructure, when poorly implemented, disrupts historic aesthetics (Salman, 2018). Proper installation of utility lines therefore constitutes the eighth parameter.

Historic buildings in Lahore typically featured elevated plinths that mediated interaction between buildings and streets, often incorporating entrance steps and raised platforms known as tharras (van der Werf, 2016; Adeeb, 2018). Preserving these plinth levels is the ninth parameter.

Encroachments diminish visual quality and functional efficiency by occupying open spaces with unplanned structures and service installations, leading to visual pollution (Shah, 2018). Preventing encroachments is identified as the tenth and final parameter.

Collectively, these ten parameters establish a structured framework for analyzing transformations within the historic urban fabric of the WCL. The research methodology developed from these parameters is presented in the following section.

Although this investigation is relevant to the entire Walled City of Lahore (WCL), examining the full area was not feasible because of limitations in time, resources, and the broader complexity of urban settlements. Therefore, a pilot assessment was undertaken across multiple neighborhoods within the WCL, and Kucha Vahrian was selected as the case-study area. This selection was based on the neighborhood’s mixture of long-term and newer residents, the sharp contrast between historic and non-historic buildings, the presence of multiple categories of heritage structures, the gradual occupation of open and shared spaces, and the influential presence of commercial builders within the locality. The literature also supports its authenticity as one of the earliest settlement points in Lahore’s formative urban history (Shahzad, 2002).

In addition, structured interviews were conducted with officials of the Walled City of Lahore Authority (WCLA) to clarify the role of this autonomous body in maintenance and conservation activities within the selected area. The Provincial Assembly of the Punjab established the WCLA under the Walled City of Lahore Act (2012). Under the provisions of this act, Kucha Vahrian falls within the WCLA’s jurisdiction (Government of the Punjab, 2017).

Implementation of the above methodology generated evidence regarding transformations in the historical urban fabric of Kucha Vahrian, which are discussed in the next section.

An aerial perspective of the WCL reveals a dense juxtaposition of houses, shops, religious structures, and shared spaces interconnected through narrow, maze-like streets. Historically, the city expanded incrementally according to community needs within a confined perimeter rather than being formed through formal planning doctrines (Shahzad, 2002). This pattern of growth within boundaries reflects an inward-oriented settlement character, also evident in the spatial layering of communal spaces enclosed by courtyard houses. Such an arrangement was common in walled cities because it reinforced privacy and created an implicit separation between public and domestic realms, supporting tranquility, intimacy, and safety (Gulzar, 2017). Over time, however, the WCL has undergone substantial transformation due to both human actions and natural processes, affecting topography as well as the configuration of built and open spaces (Shahzad, 2011). This paper examines these changes through the selected neighborhood of Kucha Vahrian, the location of which is shown in Figure 1.

To evaluate the urban fabric of the case-study area, it is necessary to consider land-use modifications that emerged during the post-partition period. Figure 2 summarizes the types of transformation observed across the 16 units examined in Kucha Vahrian. Interviews with elderly residents indicated that in 1947 the neighborhood exhibited a highly coherent built environment, land-use structure, and architectural character. In one zone, houses were arranged around a communal courtyard containing a well (khooh) for residents in what is now unit 13. This observation aligns with Adeeb (2018), who reports that neighborhoods of that period typically possessed local wells for drinking water. Field observations showed that the courtyard space formerly containing the well has been replaced by residential construction.

Similarly, a school building located at the edge of the neighborhood (units 15 and 16) ceased to operate as an educational facility in the post-partition era due to the influx of migrant families in need of urgent shelter. The school was converted into housing, and an adjacent open plot was used for new residential construction (unit 14). Moreover, the principal residence of the neighborhood (units 8–10) could previously be understood as a haveli—a large compound accommodating multiple (often related) families and sharing key spaces such as an entrance, central courtyard, and roof (Bryden, 2004). That building has since been subdivided into multiple units, thereby diminishing its former status.

The current building stock can broadly be categorized into pre-partition and post-partition structures. The former includes historic houses with traditional facades, whereas the latter consists of non-historic buildings constructed on former open spaces or replacing older structures. The ten parameters defined in the literature review were applied to all 16 units (Figure 2) to document and interpret transformations in the neighborhood’s urban setting.

Site observations indicated that surviving traditional buildings still reflect their vernacular construction identity through indigenous materials, customary facade detailing, early support systems, finely crafted doors and windows, and continuity with the original street plinth level (evident through lowered thresholds). These retained historic structures represent vernacular design principles and craftsmanship, including open windows and balconies that facilitate the entry of daylight and fresh air into interior spaces. In contrast, later non-historic structures appear visually plain and largely lack traditional characteristics in ornamentation, material selection, fenestration, structural approach, and threshold height. In addition, some older buildings no longer fully reflect their vernacular character and conflict with conservation ethics due to unsuitable retrofitting, unplanned spatial additions and encroachments, disorderly installation of service lines, and impediments to daylight and ventilation.

Evaluating the present condition of the historic urban fabric of Kucha Vahrian raised a central concern: how can the ongoing decline be resisted and reversed. This prompted a detailed reading of the Walled City of Lahore Act (2012), the statutory framework that defines the scope, regulatory control, and leadership authority of the Walled City of Lahore Authority (WCLA) (Provincial Assembly of the Punjab, 2012). Recognizing both the administrative institution and the public as principal stakeholders in this legal framework, the authors engaged two groups through interviews, adopting distinct modes of questioning for each. Clauses of the Act that were directly relevant to conservation and regulation were reworked into structured interview questions for WCLA officials, who were asked to interpret the legislation and clarify the practical powers available to them for enforcement. In parallel, discussions with mohalla residents were conducted through semi-structured and relatively informal conversations, designed to explore how residents understand WCLA provisions and whether such regulations shape everyday building decisions. Together, these interviews produced a composite picture of how the WCLA and residents perceive the same governance structure.

The interview evidence indicates that the WCLA views the WCL as a valuable cultural asset that combines historical depth with architectural significance and can be enhanced as a tourism destination. Although heritage protection is often characterized as a weakly internalized social value in Pakistan (Mumtaz, 2017), the residents of Kucha Vahrian nevertheless expressed attachment and pride in the area’s legacy. At the same time, they repeatedly voiced discomfort and self-deprecation about living in an economically marginalized neighborhood, revealing a tension between cultural pride and social stigma.

The study further revealed that residents frequently respond to shifting household needs by constructing plain additions and installing improvised utility lines on top of already weakened structures. These alterations accelerate the breakdown of facade composition and undermine structural capacity, thereby intensifying the deterioration of the wider historical fabric. In addition, large-scale new construction has increasingly occupied spaces that were formerly open or communal, reducing daylight penetration and obstructing natural ventilation across the neighborhood. Such interventions also demonstrate a marked departure from indigenous materials and traditional construction techniques. In an attempt to control these trends, the WCLA issued building regulations intended to limit additions and encroachments (Government of the Punjab, 2017). However, these regulations provide little operational guidance on appropriate traditional materials or suitable heritage-based workmanship. The study also established that residents were largely unaware of the existence of these regulations. When questioned about awareness-building activities, WCLA officials pointed to workshops and seminars conducted in high-end hotels, which were reportedly attended mainly by professionals and students. Residents, in contrast, reported no knowledge of such initiatives and implied that these events did not address their realities. This disconnect has contributed to limited training and weak awareness among residents regarding how to intervene in historic structures without harming the heritage character of the area.

A conservation pilot in another locality within the WCL, namely Gali Surjan Singh, provided a constructive model showing that heritage training and public sensitization, supported through a community-based organization (CBO), can enable successful conservation outcomes (Salman, et al., 2018). Nevertheless, the project did not translate into broader impact across the WCL, largely because there was no permanent local institution to coordinate and sustain similar efforts at scale. This limitation parallels the experience of the Orangi Pilot Project in Karachi, which cultivated long-term public trust partly because it maintained a continuous local presence (Mumtaz, 2017).

Most surveyed residents identified themselves as belonging to low-income groups and used financial constraints to justify why repair and construction work is rarely carried out in accordance with conservation-oriented architectural principles. Yet, external support from the World Bank and the Punjab government enabled the Gali Surjan Singh initiative to achieve strong architectural outcomes alongside high resident satisfaction (Salman, et al., 2018). WCLA officials, however, maintained that such funding was allocated only for that specific pilot and was not available for conservation interventions across the entire WCL.

After concluding that Kucha Vahrian has been unable to protect its historical urban fabric under current conditions, the authors conveyed this concern to WCLA officials and inquired about strategic planning for the wider WCL. Officials reported that a master conservation redevelopment plan had been produced. From the authors’ assessment, however, this document does not provide an actual conservation strategy and instead functions primarily as a current land-use plan. This suggests that, at the macro scale, the WCL reflects an enlarged version of the same pressures and outcomes observed in the case-study neighborhood. On this basis, the authors developed a set of recommendations intended to support restoration and long-term conservation within Kucha Vahrian and, by extension, across the WCL. These recommendations are presented in the next section.

Evidence from a separate conservation initiative within the WCL demonstrated effective coordination among the WCLA, the funding body, and the local community, whereas such alignment was not observed for the case-study locality examined in this paper. The central implication is that conservation practice remains largely project-driven rather than guided by sustained processes. This research therefore proposes a long-term, integrated pathway for conserving the urban fabric of the entire WCL.

A first requirement is to strengthen and redirect the research and development functions of the WCLA. This involves documenting materials currently available in the market and assessing their suitability for heritage applications, developing feasible heritage-compatible materials and techniques, and designing training workshops for both community members and local labor. It also requires identifying the most effective media channels for community counseling and defining strategies for mobilizing them, conducting a critical assessment of the WCLA’s technical capacity and specifying improvements, and producing prototype case studies that draw lessons from comparable conservation schemes.

A second requirement is to move beyond a project-by-project approach to expertise by establishing a permanent technical team within the WCLA. Such a team should include town planners, architects, conservation specialists, curators, construction managers, anthropologists, and archaeologists, rather than relying on temporary engagement of professionals for individual projects (Mumtaz, 2017). In addition, the team should operate under clearly defined terms of reference and standard operating procedures, supported by scheduled monitoring and follow-up mechanisms to ensure continuity and accountability (Feilden, 2003).

A third requirement is to develop practical trust and sustained working relationships between the WCLA and the local community. This includes identifying active community members who can form community-based organizations, following the participatory model adopted in the Gali Surjan Singh initiative (Salman, et al., 2018). It also includes facilitating group discussions among residents, conducting a strengths–weaknesses–opportunities–threats (SWOT) analysis (Feilden, 2003), and preparing proposals that are explicitly inclusive of community priorities and participation (Khan, 2015).

A fourth requirement is to counsel and sensitize the community through multiple communication channels. Religious scholars and clerics can be engaged to foster respect for the area’s multi-religious heritage and to support ethical guidance connected to civic responsibility. Heritage education should also be embedded within school curricula, including the introduction of heritage topics at the elementary level and the facilitation of workshops and informational sessions led by teachers (Qureshi, 1994). Awareness can further be expanded through print and electronic media, as well as through planning and promotion of heritage festivals, while CBO activities should be coordinated and supported to maintain continuity.

A final requirement is to implement community training programs that target both the labor force and residents. Local craftsmen and laborers should receive training in traditional and indigenous materials, compatible modern alternatives, facade repair practices, and building crafts (Qureshi, 1994). In parallel, residents should be trained on statutory provisions relevant to historic areas, common apprehensions regarding building by-laws, and the negative consequences of encroachments and alterations to established plinth levels.

This study shows that Kucha Vahrian’s historic urban fabric is under sustained pressure and is not being preserved effectively under current conditions. Although some pre-partition buildings still retain vernacular features—such as indigenous materials, traditional facade elements, original openings, and street-related plinth levels—the overall neighborhood is experiencing rapid loss of heritage character. The principal drivers are unregulated spatial additions, construction over former open and communal spaces, incompatible retrofitting, and disorderly utility installations that weaken structural integrity and degrade the visual and environmental quality of the area, particularly by reducing access to daylight and ventilation.

The governance review and interviews reveal that the WCLA recognizes the heritage value of the WCL and its potential for cultural tourism, yet a major gap persists between statutory intent and local practice. Residents are largely unaware of existing regulations, while current outreach efforts do not effectively reach the community most responsible for day-to-day building decisions. Moreover, regulations provide limited practical guidance on traditional materials and appropriate techniques, and conservation progress remains dependent on isolated, donor-supported projects rather than a continuous citywide process. Overall, the findings suggest that conserving the WCL requires a shift from short-term, project-based interventions to a long-term, integrated approach that builds permanent technical capacity within the WCLA, establishes sustained community-based structures, delivers locally accessible training for residents and craftsmen, and provides clear, actionable guidance for heritage-compatible repair, services integration, and control of encroachments.

Aamir N (2018) The rise and fall of the tradition of woodcarving in the subcontinent. Journal of the Punjab University Historical Society 31(1):161-171.

Adeeb Y (2018) Mera shehr Lahore: Barre saghir ke romanwi shehr ki dastanein (Urdu). Lahore, Pakistan: Jumhoori Publications.

Bryden I (2004) ‘There is no outer without inner space’: Constructing the haveli as home. Cultural Geographies 11(1):26-41.

Bukhari FB, Nadir R, Ghazanfar M (2016) Is modernity depleting Bhera. Lahore Journal of Policy Studies 6(September):85-110.

Cowell C (2016) The Kacchā-Pakkā divide: Material, space and architecture in the military cantonments of British India (1765-1889). ABE Journal 9-10.

Feilden BM (2003) Conservation of historic buildings, 3rd edition. Oxford, UK: Architectural Press.

Freeman C (2014) Egypt, Greece, and Rome: Civilizations of the ancient Mediterranean, 3rd edition. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Glover WJ (2007) Making Lahore modern: Constructing and imagining a colonial city. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Goad P (2005) Rahul Mehrotra. In P Goad, A Pieris, and P Bingham-Hall (Eds.), New directions in tropical Asian architecture. Sydney: Pesaro Publishing, p. 240.

Government of the Punjab (2017) Walled city of Lahore building regulations 2017. https://lgcd.punjab.gov.pk/system/files/WLCA_2012.pdf. Site accessed 14 December 2020.

Gulzar S (2017) Walled city of Lahore: An analytical study of Islamic cities of Indian subcontinent. International Journal of Research in Chemical, Metallurgical and Civil Engineering 4(1):69-73.

Haroon F, Nawaz MS, Khilat F, Arshad HS. Urban heritage of the walled city of Lahore. Journal of Architectural and Planning Research. 2019 Dec 1;36(4):289-302.

Heritage Foundation of Pakistan (2012) Peshawar heritage. http://www.heritagefoundationpak.org/mi/3/peshawar-heritage. Site accessed 16 October 2019.

Kaur R (2006) The last journey: Exploring social class in the 1947 partition migration. Economic and Political Weekly 41(22):2221-2228.

Khalid R, Sunikka-Blank M (2018) Evolving houses, demanding practices: A case of rising electricity consumption of the middle class in Pakistan. Building and Environment 143(June):293-305.

Khan SM (2015) Revitalizing historic areas: Lessons from the renovation of Saidpur Village, Islamabad. Journal of Research in Architecture and Planning 18(1):11-22.

Lynch K (1960) The image of the city. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Mumtaz SN (2017) Community based urban area conservation lessons from Pakistan. Journal of Research in Architecture and Planning 22(1):26-33.

Ovais H (2016) Architectural styles during the British raj in Lahore. International Journal of Environmental Studies 73(4):616-630.

Petropoulou E (2007) Revitalizing a historic city — the case of Nicosia. In X Casanovas (Ed.), 1st Euro-Mediterranean regional conference: Traditional Mediterranean architecture present and future. Barcelona: RehabiMed, pp. 217-219.

Petruccioli A (2007) After amnesia: Learning from the Islamic Mediterranean urban fabric. Bari, Italy: ICAR.

Provincial Assembly of the Punjab (2012) The walled city of Lahore act 2012 (Act XXXVI of 2012). https://walledcitylahore.gop.pk/building-regulations-2/. Site accessed 25 June 2020.

Qadeer MA (1983) Urban development in the Third World: Internal dynamics of Lahore, Pakistan, First edition. New York: Praeger.

Qureshi F (1994) Conserving Pakistan’s built heritage (Pakistan National Conservation Strategy sector paper no. 12). Karachi: Environment and Urban Affairs Division, Government of Pakistan, and International Union for Conservation of Nature.

Rahmaan AU (2017) Evolution of town planning in Pakistan with a specific reference to Punjab Province. Self-published paper.

Salman M, Malik S, Tariq F, Khilat F (2018) Conservation analysis of Gali Surjan Singh: A study of architectural and social aspects. Journal of Architectural Conservation 24(2):134-151.

Shah PH, Kaderi AI, Malani NS, Suryavanshi AS (2018) Reclaiming glory of Shehr-i-Khas, Srinagar — revitalization of Ali Kadal-Maharaj Ganj area. Journal of Heritage Management 3(1):87-111.

Shahzad G (2002) Lahore: Ghar, Galian, Derwaze. http://apnaorg.com/books/ghafar-shahzad/book.php?fldr=book. Site accessed 16 October 2019.

Shahzad G (2011) The impact of infrastructural services on traditional architecture and urban fabric of the walled city of Lahore. Journal of Research in Architecture and Planning 10(1):35-44.

Singh MK, Mahapatra S, Atreya SK (2009) Bioclimatism and vernacular architecture of north-east India. Building and Environment 44(5):878-888.

Singh P (2007) The political economy of the cycles of violence and non-violence in the Sikh struggle for identity and political power: Implications for Indian federalism. Third World Quarterly 28(3):555-570.

Uzun CN (2003) The impact of urban renewal and gentrification on urban fabric: Three cases in Turkey. Journal of Economic and Social Geography 94(3):363-375.

van der Werf J, Zweerink K, van Teeffelen J (2016) History of the city, street and plinth. In H Karssenberg, J Laven, M Glaser, and M van’t Hoff (Eds.), The city at eye level: Lessons for street plinths, Second and extended version. Delft, the Netherlands: Eburon Academic Publishers, pp. 36-47.