This study investigates how the features of different architectural designs can be examined through semantic analysis of web-based opinions on building design. We analyze several thousand online comments about architectural projects and propose a method for extracting and evaluating architectural design features from website text. Using a case-study approach, we focus on two main data sources: professional discussions from a Chinese online architectural forum, the Architecture Bulletin Board System (ABBS), and public comments on competing design proposals for the Zhangjiakou Olympic Stadium. By applying semantic analysis to these web texts, the study reveals salient architectural design features and systematically highlights the differences among alternative design schemes, demonstrating the potential of website-based semantic feature extraction as a tool for architectural evaluation and comparison.

The aim of this study is to identify and compare features of different architectural designs through semantic analysis of website-based comments on building design. With the widespread adoption of internet technologies, new media platforms have become central channels for the circulation of information and opinion. The expansion of mass-communication methods has shaped people’s perceptions in complex ways, both consciously and subconsciously, directly and indirectly (Chandratilake, 2003). For example, the design of a landmark building in Suzhou, China, became the target of intense online criticism, where netizens mockingly referred to it as the qiuku building due to its peculiar shape (qiuku literally means “the pants you wear in autumn,” a colloquial reference to thermal underwear). This case triggered broader online discussions about “strange buildings” on various Chinese new media platforms. Such episodes illustrate how digital media now plays an increasingly important role in architectural criticism, influencing the subject, content, form, and standards of architectural reviews (Li and Zhi, 2014). In addition, online reviews and social-media posts can provide valuable, user-generated information about professional services, including planning and architectural design, to potential clients (von Hoffen et al., 2018; Ying and Yao, 2015). These developments raise a central question: how can we systematically examine the features of different architectural design proposals using the semantic content of online comments on websites?

Recognizing that comments collected from new media platforms may help enhance the scientific rigor of planning and design evaluations (Ying and Yao, 2015), this study employs semantic analysis of web texts related to building designs from an online architectural forum. The research process involves analyzing word frequencies and constructing a domain-specific corpus of architectural features derived from these website comments. Focusing on three alternative building design proposals, the authors apply semantic analysis techniques to the corresponding online discussions and extract high-frequency, feature-revealing terms associated with each proposal. In doing so, the study demonstrates how semantic analysis of website content can be used to detect characteristic architectural design features and to differentiate systematically among competing design schemes.

Architectural commentary plays a critical role in shaping and evaluating architectural projects. From a social perspective, buildings are man-made artifacts that constitute the image of a city and are deeply intertwined with its history, geography, culture, and everyday urban life (Rossi, 1982). From the perspective of architectural production, it is increasingly necessary to collect and disseminate architectural comments through media channels even before construction begins (Joseph, 2009), underscoring that architectural criticism and architectural design practice should operate in a mutually reinforcing relationship.

Traditional methods for architectural evaluation are diverse and often rely on structured models or controlled assessment environments. Several studies have proposed models for building evaluation based on multiple criteria and elements (Lam, 2004; Lee and Chun, 2012; Liu, 2015). Franz (2003) and Münster and Berg (2015) developed models of architectural criticism and examined how these can be applied in design assessment. Amedeo and Dyck (2003) used questionnaire surveys to investigate the features of classroom spaces as part of the broader built environment rather than a single design proposal. Ryu et al. (2007) constructed virtual-reality environments to immerse users in planned spaces and to collect evaluative feedback for refining design schemes. These approaches demonstrate the long-standing interest in capturing user perceptions of architecture, though they typically involve carefully controlled instruments rather than large-scale, naturally occurring digital commentary.

Academic perspectives on building evaluation and commentary have evolved alongside these methodological developments. Hua (2009) argued that building evaluation research has shifted from focusing on scientific methods, architectural form, and construction rules toward iterative design practices driven by dialogue and open discussion. In China, subjective expressions of building evaluations have been increasingly prominent since the early 1990s (Wang, 2008). Although there is no single standard or universally accepted value judgment for evaluating buildings, the demand for robust, reliable tools and methods remains strong (Fan, 2014).

The rise of a digitally networked society has transformed how such evaluations are produced and circulated. As Lange (2011:404) notes, contemporary Western society has rapidly transitioned from being dominated by “digital immigrants” hesitant to enter the digital landscape to one in which “digital natives” shape the professional world. With the expansion of internet use, new media platforms now provide abundant channels for expressing architectural comments and opinions, bringing more diverse social groups into architectural feedback processes. New media has opened valuable pathways for communication between architects and the public, enabling citizens to participate in the design process by contributing information that can support decision-making (Shen and Kawakami, 2007). Increasingly, people rely on virtual built environments and digital platforms to collect architectural comments and to evaluate environments (Cheng, 2016). However, existing research on architectural commentary in new media has tended to emphasize theoretical reflections more than concrete, systematic analysis techniques. In this context, developing methods that employ semantic analysis of website text to evaluate building proposals offers a promising way to extract relevant information from mass-media reviews and use it effectively in architectural design analysis.

Semantic analysis of user comments has already been applied across a range of topics relevant to the built environment and beyond. For example, used semantic analysis to examine how individuals understand various apartment floor plans and to identify their concerns about specific spatial requirements. Neto et al. (2016) used a semantic differential (SD) survey to evaluate how different densities of physical elements affect participants’ impressions. Other work has applied semantic and related techniques directly to improving built environments: Abanda et al. (2013) argued that semantic web technologies are essential for evaluating and enhancing the built environment, while Cervinka et al. (2014) invited participants to assess hospital gardens using SD and psychological rating scales and then formulated design recommendations based on the findings.

Beyond architecture, semantic analysis has been widely used to understand markets and social behavior, illustrating its potential as a tool for extracting meaningful features from large bodies of online text. Fowler and Pitta (2013) explored the use of text analytics and semantic web technologies to extract consumer preferences from user-generated media. Walchhofer et al. (2009) carried out the Semantic Market Monitoring (SEMAMO) project, which leveraged the growing volume of information from internet-based sales and marketing channels for market research. Semantic technologies have also supported deeper political participation: Anadiotis et al. (2010) examined how semantic web technologies, in conjunction with emerging Web 2.0 usage patterns, enable new forms of e-participation, while Charalambous et al. (2014) identified and assessed the contributions semantic technologies can make to online collaboration platforms.

Taken together, these strands of research show that building evaluation has evolved into a multicontext, multichannel system, and that the proliferation of new media platforms has accelerated this transformation. Yet, despite the demonstrated potential of semantic analysis in other domains, its application to the comparison of different architectural designs using large volumes of digital comments remains underdeveloped. By applying semantic analysis to architectural commentary from internet forums and other website-based sources, it becomes possible to directly and efficiently identify spatial perceptions and design-related concerns, foster broader public participation, and support more nuanced judgments about the value and distinguishing features of architectural designs.

In this research, the method for examining features of architectural designs is grounded in the semantic analysis of website-based, crowdsourced digital comments. The central aim is to capture collective opinion on architectural projects as it emerges in online discussions, thereby using the web as a large-scale, naturally occurring evaluation environment. Such an approach aligns with the broader notion of crowdsourcing, in which key tasks are outsourced to an undefined network of contributors through an open call (Howe, 2006); for example, clients might crowdsource specific design tasks or invite large online communities to review and compare alternative design proposals (LaToza and van der Hoek, 2016). Consistent with this logic, the present study conducts a text-mining–based semantic analysis of website comments on architecture to extract and evaluate architectural design features.

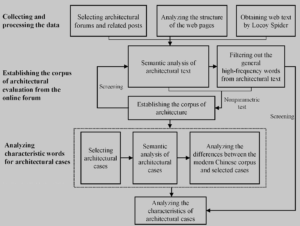

As von Hoffen et al. (2018) note, social media and other digital platforms can serve as powerful instruments for holistic sentiment analysis within a given domain, and the analysis of crowdsourced comments from professionals and users can provide valuable input for improving designed products and services. Building on this insight, the present study follows a series of steps to examine architectural design features through semantic analysis of website text (Figure 1). First, comments are harvested from an online architectural forum. These comments are segmented into words, and word frequencies are calculated. By comparing these frequencies to those in a modern Chinese reference corpus, common Chinese words that are not specific to the architectural domain are filtered out, yielding a corpus of architectural evaluation terms derived from the forum. This corpus is then used to identify characteristic feature words for specific architectural cases. The following subsections describe this process in detail.

The first step in constructing a website-based semantic analysis pipeline is to select a professional forum that provides abundant, high-quality architectural discussions as a data source. After inspecting the underlying code of the chosen website, the authors used the Locoy Spider software to automatically extract architectural themes and associated comments from the forum. Because this is a professional architectural forum, the resulting crowdsourced comments primarily reflect the views of individuals who are actively interested in architectural design. Consequently, the opinions of those who are indifferent to such topics are naturally excluded from the dataset. While acknowledging documented differences between expert and nonexpert spatial perceptions (Bates-Brkljac, 2013), the authors contend that the professional commentary of architects and other design-engaged users—especially when aggregated through crowdsourced online discussion—constitutes a crucial input to design decision-making processes.

In this study, a corpus is understood as an organized set of texts or terms; the architectural corpus specifically refers to a collection of “seed” words or expressions that describe architectural features, typically recorded in their base form (e.g., “shape” rather than “shapes”). On the selected architectural forum, the content appears as Chinese sentences and short passages. The authors used Jieba (http://www.oschina.net/p/jieba) for word segmentation, dividing sentences into discrete tokens and compiling lists of architectural seed words extracted from the forum comments. Next, they used WordsCount 3.5 (developed by Agile Studio; http://www.yuneach.com/soft/WordsCount.asp) to compute word frequencies for these seed terms.

As expected, many words with high frequencies in modern Chinese also appear frequently in the architectural forum text, even though most of these are not specific to the architectural domain. It is therefore necessary to distinguish general, high-frequency Chinese words from those that meaningfully characterize architectural design. To do so, the authors compared two corpora: the modern Chinese reference corpus and the candidate corpus of architectural evaluation terms from the forum. A frequency table for the modern Chinese corpus was obtained from a professional corpus website (www.cncorpus.org). Word frequencies in both the modern Chinese corpus and the forum corpus were normalized, and the two sets of standardized frequency data were then imported into IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 20.0 (www.ibm.com/products/spss-statistics) for nonparametric analysis. By testing the statistical significance of the differences in word frequencies, the authors identified terms whose usage patterns in the forum diverged significantly from general usage in modern Chinese. Only words that passed this significance test were retained as architectural feature terms in the forum-derived corpus.

To further separate professional architectural terminology from everyday language, the authors then focused on identifying architectural terms that are especially important within the crowdsourced text. Although term frequency–inverse document frequency (TF–IDF) is a widely used measure of word importance in text mining, conventional TF–IDF-based methods are generally geared toward classifying or clustering words and tend to highlight relationships among similar terms rather than isolating strongly domain-specific words (Zhang et al., 2011). Consequently, an alternative approach was needed to determine whether a term in a document or corpus functions as a salient professional architectural feature.

For this purpose, the authors adopted a TextRank-based algorithm to compute the importance of seed words and expressions in the crowdsourced forum text. Let \(w_i\) denote a seed word and \(S(w_i)\) its importance score. The score is defined as \[S(w_i) = (1 – d) + d \sum_{w_j \in \text{In}(w_i)} \frac{1}{\lvert \text{Out}(w_j) \rvert} \, S(w_j),\] where \(S(w_i)\) denotes the importance of seed word \(w_i\), \(S(w_j)\) is the importance of a seed word \(w_j\) that is linked to \(w_i\), \(d\) is a damping coefficient typically set to \(0.85\), \(\text{In}(w_i)\) is the set of seed words that point to \(w_i\), \(\text{Out}(w_j)\) is the set of seed words to which \(w_j\) points, and \(\lvert \text{Out}(w_j) \rvert\) is the number of elements in that set. The algorithm iteratively updates the values of \(S(w_i)\) for all seed words until convergence is reached and the importance scores stabilize. Using these scores, the authors ranked seed words and expressions from highest to lowest importance.

After obtaining the TextRank-based importance ranking, the authors again consulted the modern Chinese corpus frequency table to exclude any seed words that still showed high frequency in general language use. The remaining terms were adopted as the final corpus of architectural design features derived from the forum. To make this corpus analytically useful for examining specific design proposals, the authors then grouped the seed words into ten categories: building type, building function, building exterior, site layout, structural material, spatial layout, design process, building component, architectural concepts, and building implementation (Table 1).

| Category | High-Frequency Words |

|---|---|

| Building Type | Architecture, Villa, Residential Community, Hotel, University, School, Library, Office Building, Museum, Hospital, Church, Commercial Street, Tall Building, Building Complex, Dwelling |

| Building Function | Function, Residence, Office, Business, Culture, Learning, Tourism, Entertainment, Catering, Practicality |

| Exterior & Form | Style, Form, Façade, Shape, Volume, Massing, Scale, Proportion, Contour, Line, Detail, Appearance, Image, Decoration, Color, Texture, Light, Streamlined, Unified, Unique |

| Site & Context | Site, Entrance, Square, Landscape, Garden, Park, Green Space, Environment, Street, Road, Transportation, Urban, Village, Ecological |

| Structure & Material | Structure, Material, Concrete, Steel, Glass, Brick, Wood, Stone, Metal, Technology, Engineering |

| Spatial Layout | Space, Layout, Plan, Room, Courtyard, Area, Circulation, Orientation, Living Room, Bedroom, Kitchen, Bathroom, Corridor, Staircase, Basement, Flexible, Comfortable |

| Design Process | Design, Concept, Plan, Drawing, Model, Chart, Architect, Designer, Client, Rendering |

| Building Components | Wall, Window, Door, Roof, Stair, Balcony, Column, Elevator, Skylight, Curtain Wall, Terrace, Furniture |

| Architectural Concepts | Concept, Theme, Idea, Atmosphere, Innovation, Tradition, Art, Symbolism, Regional, Sustainable |

| Implementation | Construction, Cost, Feasibility, Reality, Structure, Energy-Saving, Practical |

The procedure for identifying characteristic words for a particular architectural case largely mirrors the process used to construct the forum-based corpus of architectural features. First, comments referring to a specific design proposal were collected from the online forum. These case-specific comments were segmented into words using Jieba, and word frequencies were computed with WordsCount. The frequencies of the architectural words in the case-specific comments and the corresponding frequencies in the modern Chinese corpus were then normalized.

Next, the TextRank algorithm was applied to the case-specific comments to compute the importance of the architectural words within that subset of the forum text. Using the modern Chinese corpus word-frequency table, the authors removed any terms that still had high frequencies in the general language corpus. The remaining terms were thus identified as characteristic words for the particular architectural design proposal. These characteristic words were then categorized according to the same ten feature groups described above. Finally, the authors calculated the total frequency of words within each category and compared the category-wise distributions across different design proposals. In this way, the semantic analysis of website-based comments was used to assess which aspects of each design were most salient and attractive to forum participants, thereby revealing and comparing the features of alternative architectural designs.

In the context of new media platforms, web-based architectural forums provide an open arena in which people from diverse backgrounds can comment on building proposals and design schemes. In this study, two principal text sources were used. First, the authors collected 4,401 posts and 32,801 architectural comments on a wide range of topics from the architectural-design and architectural-communication modules of a professional Chinese online forum, the Architecture Bulletin Board System (ABBS; http://www.abbs.com.cn/bbs/). These data were used to construct a professional corpus by filtering words according to their frequencies relative to a modern Chinese reference corpus. Second, the authors assembled a set of public comments on five design proposals for a stadium to be built in Zhangjiakou as a main venue for the 2022 Winter Olympics. The five proposals attracted substantial public attention; in total, 4,662 comments on the Zhangjiakou Olympic Stadium designs were collected from a public website that was subsequently closed after the voting process. The architectural terms extracted from ABBS were then used to compare and interpret the specific features of the five stadium proposals through the lens of this body of public comments.

The authors applied text-mining tools (including the TextRank algorithm) to segment the crowdsourced web comments into words and to calculate both the importance and frequency of each term. Word frequencies in the two word lists (the ABBS forum and the modern Chinese corpus) were normalized using the following transformation. Let \(f_{ij}\) denote the raw frequency of word \(i\) in word list \(j\), and let \(s_{ij}\) be the corresponding normalized value: \[s_{ij} = \frac{f_{ij} – f_j^{\min}}{f_j^{\max} – f_j^{\min}},\] where \(f_j^{\min}\) and \(f_j^{\max}\) are, respectively, the minimum and maximum frequencies observed in list \(j\), \(i = 1,2,\dots\), and \(j = 1,2\). Next, the authors selected as samples the 50 most frequent words in the modern Chinese corpus. The frequencies of these words in both the forum word list and the modern Chinese corpus were normalized using the above equation and entered into SPSS as two groups for nonparametric analysis to test the significance of the differences between them. In particular, the authors examined the test statistic \(z\) and the associated probability value Sig. computed by SPSS, and compared these values to standard significance thresholds to determine whether the two groups of sample data differed meaningfully.

The analysis yielded a test statistic of \(z = 114.477\) and an associated probability value of \(\textit{Sig.} = 0.000\), indicating a highly significant difference between the two corpora. On this basis, the authors concluded that architectural comments exhibit distinctive patterns of word usage relative to general modern Chinese.

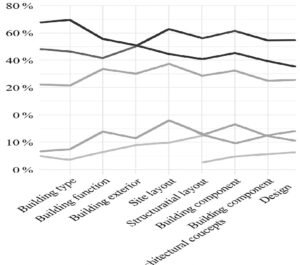

To construct the architectural feature corpus, the authors then removed any words whose standardized frequency values \(s_{ij}\) in the ABBS forum list were less than \(0.001\) and/or lower than their corresponding values in the modern Chinese corpus. The remaining terms were assigned to the ten categories introduced earlier and used to define the corpus of architectural features derived from the forum: building type, building function, building exterior, site layout, structural material, spatial layout, design process, building component, architectural concepts, and building implementation (Table 1). Figure 2 compares the word-frequency data across these ten categories for the two corpora.

The crowdsourced comments on the Zhangjiakou Olympic Stadium design proposals were analyzed using the same procedure applied to the ABBS forum in order to derive architectural characteristic words. The government released five alternative design schemes for public review. However, Designs 1 and 4 received relatively few specific comments, so the analysis focused on Designs 2, 3, and 5, which together attracted 4,319 design-specific comments from the public. These comments formed the basis for extracting and comparing characteristic words associated with each proposal (Table 2).

The authors first collected the lists of comments on each design from the public website and computed word frequencies. Words were then ordered from highest to lowest frequency, and, for each design, the 30 most frequent terms that clearly related to architectural characteristics were selected (Table 2). The frequencies of these terms in the modern Chinese corpus and in the comments on each design proposal were then compared. Words that appeared substantially more frequently in the comments on a particular design than in the reference corpus were interpreted as reflecting characteristic features of that design.

| Design | No. of Comments | Characteristic Words |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | 965 | Splendid, Reasonable, Comprehensive, Venue, Characteristic, Modeling, Theme, Complete, Vigor, Space, Function, Realistic, Energy saving, Advanced, Green, Perfect, Elegant, Beautiful, Cost, Region, Idea, Massive, Unique, Grand, Concise, Suitable, Entertainment, Designer, Coordination, Culture |

| 3 | 132 | Splendid, Comprehensive, Meaning, Unique, Times, To the point, Theme, Originality, Elegant, Shocked, Vision, Brilliant, Pure, Comfortable, Simple, Workable, Idea, Atmosphere, Pretty, Modeling, Novel, Economical, Function, Streamline, Combination, Pragmatic, Beautiful, Art, Plant, Character |

| 5 | 3,222 | Splendid, Theme, Comprehensive, Practical, Reasonable, Beautiful, Elegant, Realistic, Idea, Venue, Novel, Perfect, Affordable, Economical, Characteristic, Space, Concise, Spirit, Complete, Advanced, Function, Modeling, Style, Construction cost, Standout, Ecological, Fashion, Green, View, Comfortable |

This analysis enabled the authors to extract core information from a large body of public comments without the need to manually read through all of the text. The resulting visualization and categorization made the features and differences among the three design proposals clear and interpretable, thereby allowing public opinions to be expressed and understood more effectively.

The characteristic words for each design proposal were then sorted into the ten feature categories listed above, as shown in Table 3. Figure 3 depicts the categorical ratios of characteristic words drawn from the design-proposal comments and from the ABBS architectural forum comments. The figure shows that the public placed considerably greater emphasis on building exterior and architectural concepts than did the commenters on ABBS. Conversely, on the ABBS forum, architects devoted more attention to spatial layout, design process, and building type—topics that appeared less prominently in the public comments on the stadium proposals, particularly the first two categories.

| Category | Design 2 | Design 3 | Design 5 |

| Building Type | Venue | – | Venue |

| Building Function |

Emphasis on practical qualities

(Reasonable, Function), cultural aspects (Entertainment, Culture), and holistic appeal (Comprehensive) |

Focus on functional

comprehensiveness (Comprehensive, Function) |

Strong functional focus

(Practical, Reasonable, Function, Comprehensive) |

| Building Exterior |

Rich aesthetic vocabulary:

grandeur (Splendid, Massive, Grand), elegance (Elegant, Beautiful), formal clarity (Concise, Complete), and distinct identity (Unique, Characteristic, Modeling) |

Expressive and emotional

response: visual impact (Splendid, Vision, Brilliant), simplicity (Pure, Simple), beauty (Beautiful, Pretty), and innovative form (Streamline, Modeling, Combination) |

Balanced aesthetic appeal:

beauty (Splendid, Beautiful, Elegant), distinction (Characteristic, Standout), formal quality (Concise, Complete, Style), and sculptural form (Modeling) |

| Site Layout |

Contextual integration

(Coordination, Suitable) and environmental consciousness (Green) |

Minimal commentary;

notable mention of natural elements (Plant) |

Clear environmental priorities

(Ecological, Green) and visual considerations (View) |

| Structural Material | – | – | – |

| Spatial Layout |

General mention of spatial

quality (Space) |

Focus on user experience

(Comfortable) |

Combination of spatial

quality and comfort (Space, Comfortable) |

| Design Process |

Recognition of the designer’s

role (Designer) |

– | – |

| Building Component | – | – | – |

| Architectural Concepts |

Conceptual focus on thematic

development (Theme, Idea), technological aspiration (Advanced), and regional relevance (Region) |

Diverse conceptual engagement:

originality (Originality, Novel), emotional impact (Shocked, Atmosphere), artistry (Art, Character), and timeliness (Times, To the point) |

Forward-looking concepts:

novelty (Novel, Fashion, Advanced, Spirit) centered on core ideas (Theme, Idea) |

| Building Implementation |

Practical concerns:

feasibility (Realistic), sustainability (Energy saving), and budget (Cost) |

Pragmatic and economical

approach (Workable, Pragmatic, Economical) |

Strong emphasis on cost

and practicality (Realistic, Affordable, Construction cost, Economical) |

From these comparisons, the authors concluded that architects and lay publics tend to focus on different aspects when evaluating buildings. Applying the proposed semantic-analysis method to identify such differences can help clarify the social requirements for a particular building and thereby enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of the architectural design process. In China, architects are often criticized for failing to understand the true expectations of their clients, and public perceptions of buildings are frequently underrepresented in design decision-making. Empirical studies of the kind presented here offer a way to reveal the properties of a design and to improve the evaluation of design alternatives.

Among the three proposals analyzed in detail, Design 5 received the most votes on the public website and was ultimately selected. The characteristic words associated with Design 5 included “splendid,” “theme,” “comprehensive,” “realistic,” “beautiful,” and “elegant.” Apart from “splendid,” which was the highest-frequency term across all three options, Design 5 was perceived as strongly emphasizing its theme of “ice and passion” and as aiming to create a stadium with comprehensive functions. Public comments also suggested that it was regarded as a more practical option, being relatively economical and suitable for public use after the Olympics. In addition, Design 5 was seen as possessing a beautiful, elegant, and distinctive appearance. Overall, the characteristic words linked to Design 5 reflected the public’s awareness of the design and acknowledged both its refinement and its practicality and broad appeal.

With the rapid development of new media platforms, crowdsourcing has become a practical means of collecting both public and professional opinions on design proposals and comparing the features of different architectural schemes. This study proposes a web-based semantic analysis approach as a new way of thinking about how architectural design features can be examined through online commentary. By leveraging the large volume of user-generated text available on internet forums and related platforms, the method provides a direct and efficient way to analyze architectural comments and to identify salient features of competing design proposals. The integration of crowdsourced data and semantic analysis encourages architectural discourse to adapt to the evolving new media environment, enabling architects to grasp public concerns more quickly and efficiently. In turn, this can promote the development of architectural design by allowing the most informative comments to feed into design decision-making processes.

At the same time, the method has several limitations. First, the process of word matching still requires refinement. Certain concepts are expressed most clearly through multiword expressions or short phrases, rather than isolated single words. For example, the word “cost” often appears in conjunction with qualifiers such as “high” or “low,” and these combinations should ideally be treated as unified expressions to capture their full meaning, whereas the present study considered words individually. Second, some terms are inherently ambiguous and can take on different meanings in different contexts. For instance, the word “angle” can refer to a geometric property of space but can also denote a perspective or point of view. The method employed here cannot fully resolve such semantic ambiguity.

Future work could extend this approach by exploring the function of words and phrases in richer contextual settings and by improving the criteria and procedures for selecting source corpora used in architectural evaluation. Enhancements in these areas would make the analysis more robust, scientific, and comprehensive. As user populations on new media platforms continue to grow and semantic-analysis techniques become more sophisticated, the examination of internet-based texts is likely to play an increasingly important role in architectural evaluation. This methodological framework can assist architects in assessing design proposals for new buildings, comparing crowdsourced comments on alternative schemes, and tracking how perceptions of similar architectural designs evolve over time, thereby providing insight into broader trends in participation and discourse on architectural forums.